London is enchanting. I step out upon a tawny coloured magic carpet, it seems, and get carried into beauty without raising a finger.

Virginia Woolf Diary, 26 May 1924

Virginia Woolf’s Bloomsbury: 46 Gordon Square and 29 Fitzroy Square

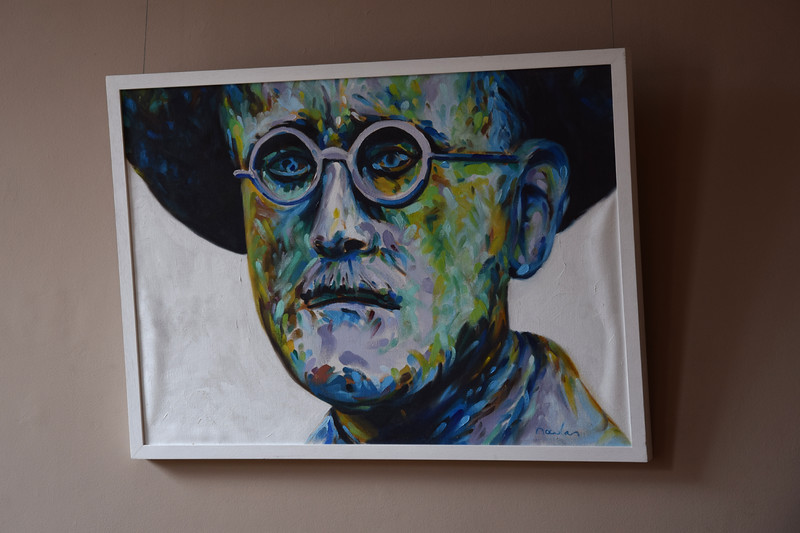

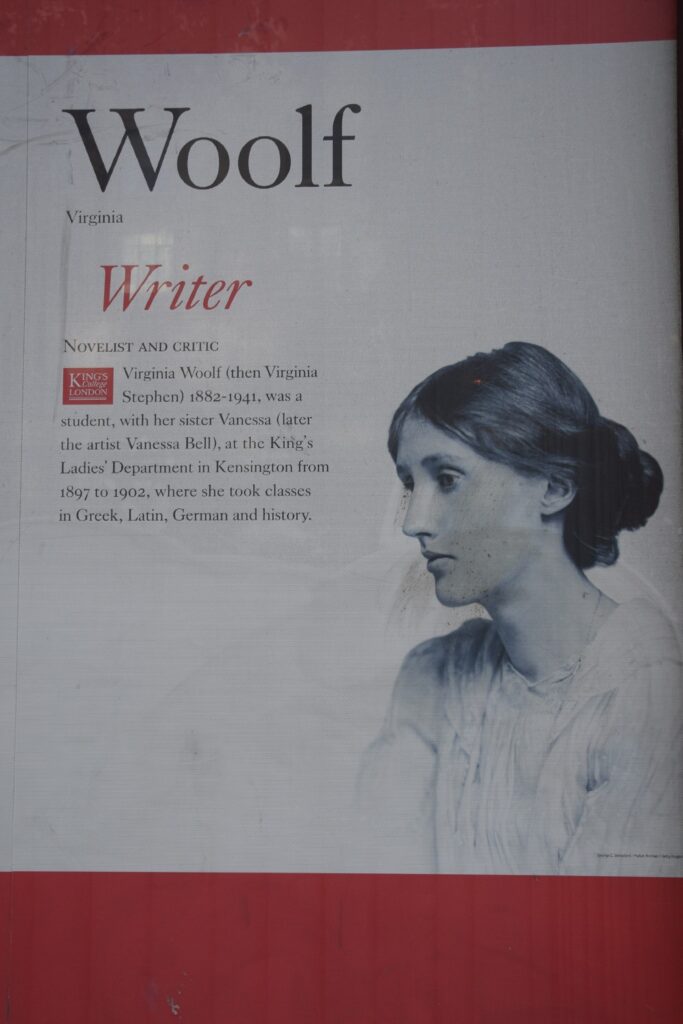

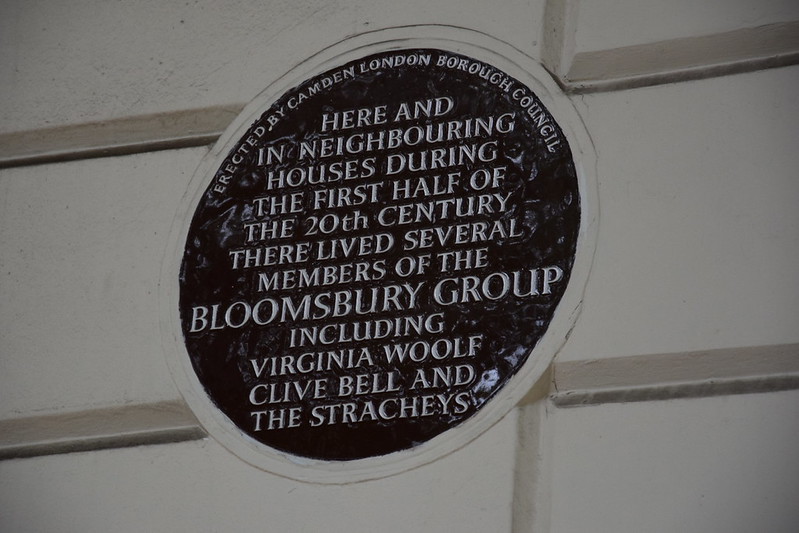

Walking through Bloomsbury today, it is easy to see calm squares, elegant terraces, and university buildings. At the beginning of the twentieth century, however, this part of London represented something far more radical. For Virginia Woolf, moving here meant leaving behind the strict world of her upbringing and beginning a new life shaped by work, independence, and conversation.

Virginia grew up at Hyde Park Gate in Kensington, a respectable address that offered comfort but also imposed control. Family life there followed fixed rules, especially for women, and daily routines were shaped by duty and supervision. After the deaths of her parents, the house became emotionally heavy, filled with mourning and constant concern about Virginia’s health. Although she longed to return to books and writing, decisions about her life were often made by others. Over time, Hyde Park Gate came to represent a closed and restrictive world from which she needed to escape.

That escape began with Bloomsbury.

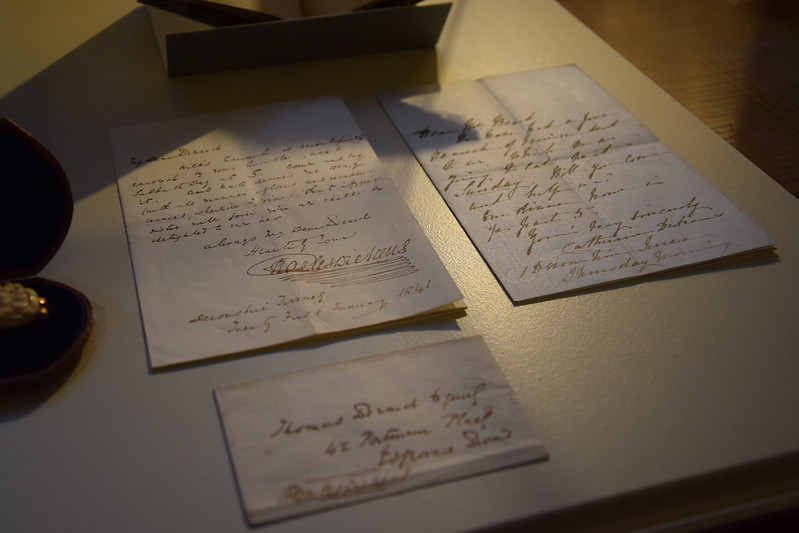

In the winter months preceding Leslie’s death, the decision had been taken for the Stephens to sell the gloomy house in Hyde Park Gate with all its associations and move to a Georgian terraced house in the less reputable but cheaper neighbourhood of Bloomsbury. Vanessa oversaw the move to 46 Gordon Square that October, while Virginia was staying with her Aunt Caroline Emelia Stephen at Cambridge, then with the Vaughan family at Giggleswick Hall, in Yorkshire. […] It was light and airy, clear from clutter, with a view across the trees in the square. […] There was an L-shaped sitting room on the first floor and Vanessa and Virginia had a study, with Thoby, who had just begun reading for the bar, settled on the ground floor. Virginia’s was equipped with a new sofa and desk, ready for her return. […] Dr Savage was concerned that Virginia should not return to London too soon, but the sisters overruled him and when Virginia arrived that November, she found the house ‘the most beautiful, the most exciting, the most romantic place in the world’. […] For the first time, paradoxically significant in preserving her freedom, Virginia had a lock on her bedroom door.

Amy Licence, Living in Squares, Loving in Triangles: The Lives and Loves of Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group

Gordon Square: light, freedom, and work begins (1905–1907)

Although the Stephen siblings moved into Gordon Square in October 1904, Virginia did not join them immediately. After her father’s death earlier that year, she suffered a serious mental breakdown and, on medical advice, was kept away from London. Only in early 1905 was she considered well enough to return and begin her life in Bloomsbury.

Once settled at Gordon Square, Virginia lived with her sister Vanessa and her brothers Thoby and Adrian. For Virginia, the most important change was having a space of her own. For the first time in her life, she had rooms arranged entirely for reading and writing. From her upper-floor rooms, she looked out over the trees of the square, a view that became closely connected with her sense of freedom and creative possibility.

This new setting made sustained work possible. During her time at Gordon Square, Virginia began publishing regularly as a literary reviewer, especially for The Guardian. Writing reviews provided both income and discipline, helping her develop confidence and a professional identity. At the same time, she experimented with fiction, producing early short stories that explored the contrast between the respectable world she had left behind and the freer atmosphere of Bloomsbury.

Alongside journalism, Virginia also taught at Morley College for working men and women. She lectured on books, art, and history, gaining experience in explaining ideas clearly and addressing audiences beyond her own social circle. Although the work was demanding, it gave structure to her days and broadened her understanding of readers and listeners.

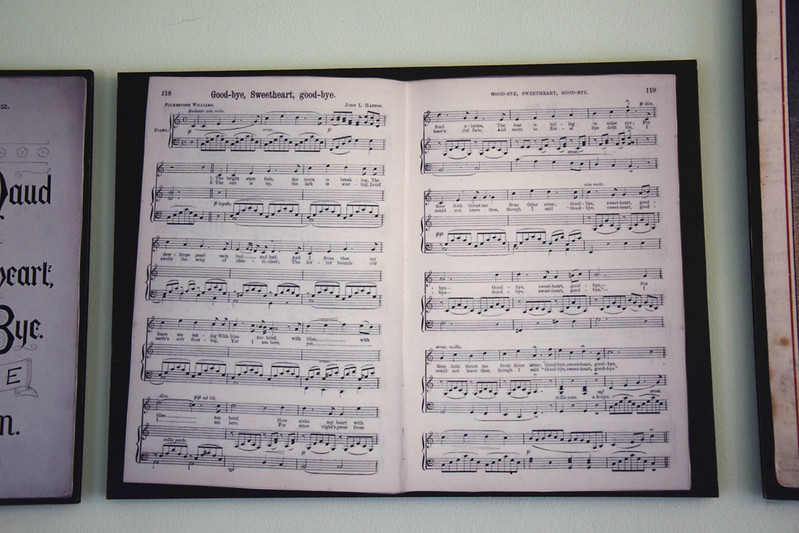

Daily life at Gordon Square supported this working rhythm. The siblings deliberately abandoned many social conventions they had grown up with. Formal visiting rituals disappeared, and life was organised around reading, writing, and discussion rather than obligation. Virginia also began walking alone through London, exploring streets, bookshops, galleries, lectures, and concerts. These walks sharpened her attention to everyday urban life and later became an important element of her writing.

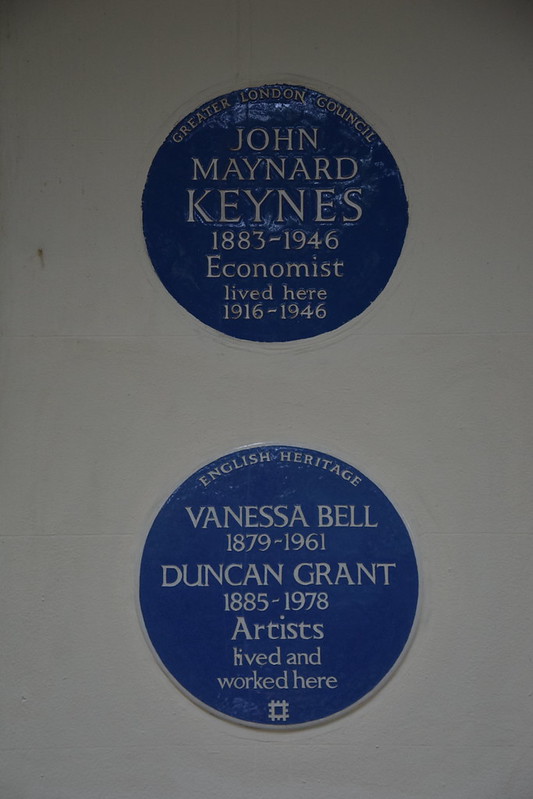

It was also at Gordon Square that the Bloomsbury Group began to take shape. Thoby Stephen, missing the intensity of Cambridge conversations, invited his friends to the house on Thursday evenings. These informal gatherings gradually became a regular meeting place for young writers and thinkers. Discussion focused on literature, philosophy, and ethical questions rather than social display. When artists later joined through Vanessa’s circle, Bloomsbury expanded beyond literature into visual art and design.

The Gordon Square years were short but intense. In the autumn of 1906, the siblings travelled to Greece. Shortly after returning to London, Thoby fell ill and died on 20 November 1906. Only two days later, Vanessa accepted Clive Bell’s marriage proposal. The household that had supported shared beginnings and collective work could no longer remain unchanged.

Fitzroy Square: independence, pressure, and the first novel (1907–1911)

In March 1907, Virginia and her younger brother Adrian moved to 29 Fitzroy Square, still within Bloomsbury but deliberately separate from Gordon Square. This move marked a new stage. Virginia was no longer part of a sibling household; she was now shaping her life more independently, both personally and professionally.

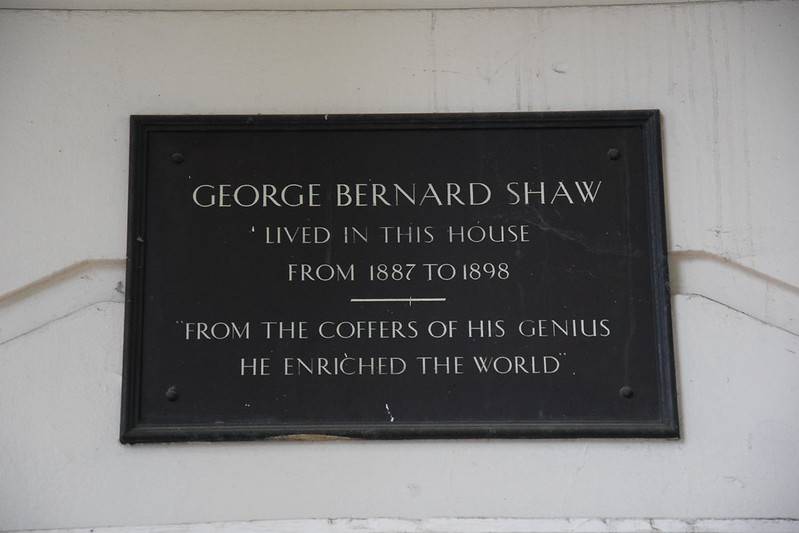

Fitzroy Square was louder and less fashionable than Gordon Square. The house required improvements, and money was often tight. Yet the move brought greater autonomy. Virginia ran her own household and had full control over her working space, occupying an entire floor filled with books, papers, and furniture chosen according to her own taste. The building itself had a literary past, having previously been home to George Bernard Shaw before his marriage.

Work continued steadily. During her years at Fitzroy Square, Virginia wrote regularly for The Times Literary Supplement while continuing her reviewing work elsewhere. Journalism remained central to her professional life, providing income and sharpening her critical voice. At the same time, she began serious work on her first novel, initially titled Melymbrosia, later published as The Voyage Out. This period marked her transition from reviewer to novelist.

Life at Fitzroy Square was not easy. Noise, financial pressure, and emotional strain were constant, especially after the loss of her brother and changes in her relationship with Vanessa. Yet Virginia remained productive. Writing became both a discipline and a form of stability, giving shape to her days and direction to her thoughts.

Virginia lived at Fitzroy Square until October 1911, when the lease ended. By then, she had established herself as a working writer and was ready to move on again, both physically and creatively.

Bloomsbury as a place of work and ideas

Seen together, Gordon Square and Fitzroy Square show how closely Virginia Woolf’s life and work were tied to the places she lived. Gordon Square made writing possible by offering light, space, and intellectual companionship. Fitzroy Square tested her independence and pushed her towards larger ambitions, including her first novel. These London addresses were not simply backdrops to her life but active working environments that shaped her habits, her discipline, and her sense of what it meant to be a writer.

Walking through Bloomsbury

All photographs by the author.

This account draws on biographical and historical studies of Virginia Woolf and her circle, particularly those that explore the relationship between place, daily life, and creative work. The books listed below were consulted in shaping this narrative and offer further context for readers who wish to explore Woolf’s London in greater detail.

- Lee, Hermione. Virginia Woolf. Chatto & Windus, 1996.

- Macaskill, Hilary. Virginia Woolf at Home. Pimpernel Press, 2019.

- Licence, Amy. Living in Squares, Loving in Triangles: The Lives and Loves of Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group. Amberley, 20215

- Hill-Miller, Katherine C. From the Lighthouse to Monk’s House: A Guide to Virginia Woolf’s Literary Landscapes. Duckworth, 2001.

- Woolf, Virginia. A Writer’s Diary. Delphi Classics, 2017.

The first part of the series can be read here: Virginia Woolf’s London – A Literary Guide to the City (Part 1)