Small Things Like These – a quiet Christmas story with a sharp edge

Christmas is coming. And maybe this time, instead of Dickens, we could read Claire Keegan. Instead of A Christmas Carol, Small Things Like These, a Booker Prize finalist from three years ago. A moving story full of Christmas spirit, about the power of everyday choices. How small acts of kindness can save lives and stand against hypocrisy and evil – the institutionalised violence done in the name of a religion whose first and greatest commandment is to love your neighbour…

The Good Shepherd nuns, in charge of the convent, ran a training school there for girls, a providing them with basic education. They also ran a laundry business. Little was known about the training school, but the laundry had a good reputation. (…) Reports were that everything that was sent in, whether it be a raft of bedlinen or just a dozen handkerchiefs, came back same as new.

There was other talk, too, about the place. Some said that the training school girls, as they were known, weren’t students of anything, but girls of low character who spent their days being reformed, doing penance by washing stains out of the dirty linen, that they worked from dawn til night. The local nurse had told that she’d been called out to treat a fifteen-year-old with varicose veins from standing so long at the wash-tubs. Others claimed that it was the nuns themselves who worked their fingers to the bone, knitting Aran jumpers and threading rosary beads for export, that they had hearts of gold and problems with their eyes, and weren’t allowed to speak, only to pray, that some were fed no more than bread and butter for half the day but were allowed a hot dinner in the evenings, once their work was done. Others swore the place was no better than a mother-and-baby home where common, unmarried girls went in to be hidden away after they had given birth, saying it was their own people who had put them in there after their illegitimates had been adopted out to rich Americans, or sent off to Australia, that the nuns got good money by placing these babies out foreign, that it was an industry they had going.

Claire Keegan, Small Things Like These

Breaking the silence – voices that challenged Ireland’s moral order

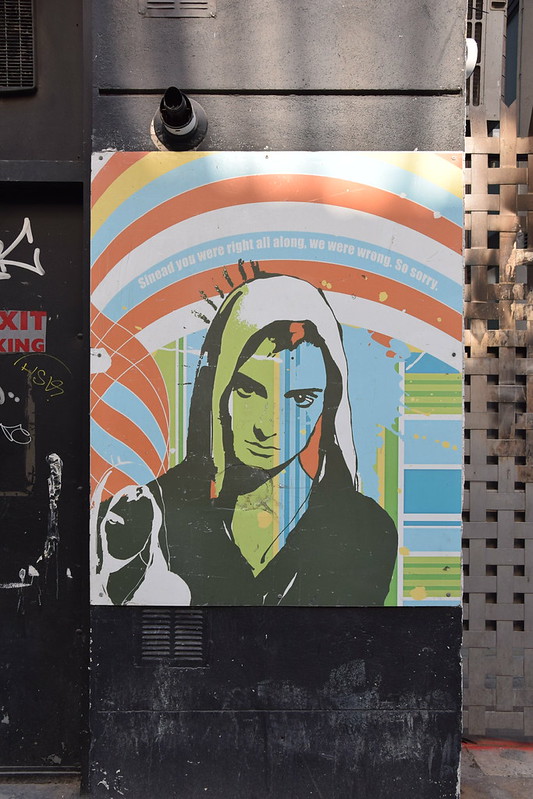

When the main character of this short novel, coal delivery man Bill Furlong, goes through the convent gate, it is 1985. Seven years later, on 3 October 1992, Sinéad O’Connor tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II on Saturday Night Live. People saw this as blasphemy, and it ruined her career. She was criticised for saying out loud what half the world now talks about.

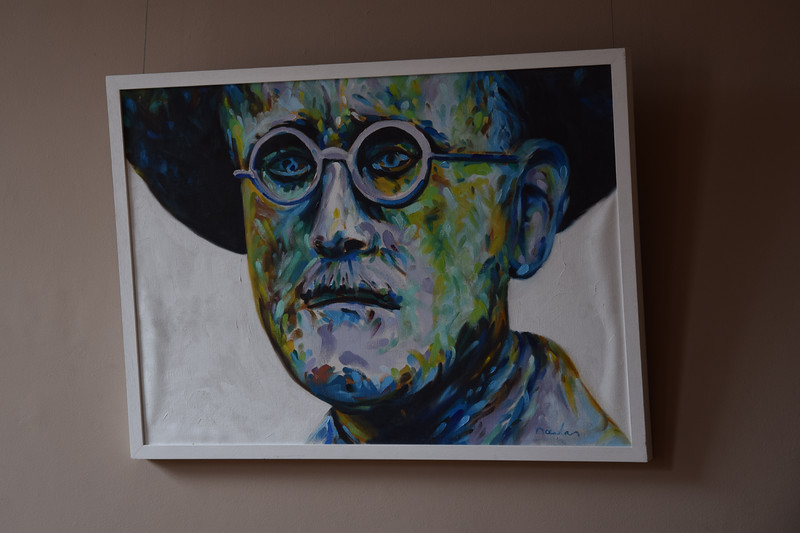

Interestingly, in James Joyce’s story The Sisters, published in 1904 in The Irish Homestead Journal (and included ten years later in the collection Dubliners), the nine-year-old narrator wonders why the death of his intellectual and spiritual mentor, Father James Flynn, brought him relief. From the half-spoken conversations among the adults, we learn that the priest had some secret that everyone supposedly knew about, but no one spoke of directly. The hints, however, are quite clear (at least from today’s perspective). They paint a picture of a depraved clergyman who harmed a child who trusted him. One of the characters sums it up by saying:

It’s bad for children. My idea is: let a young lad run about and play with young lads of his own age and not be…

James Joyce, Sisters

Joyce did not finish that sentence at the time. The Irish had to wait several more decades. The silence was finally broken by actor and performer Gerard Mannix Flynn, who, as a teenager, spent two years in an industrial school in Letterfrack, run from the late 19th century by the Catholic organisation Christian Brothers. His book, Nothing to say (published in 1983), became one of the first voices speaking out about the sexual abuse of minors by clergy.

Writing the story was frightening: I knew that certain sections of Irish society would reject the notion that the Christian Brothers could do anything wrong. As for the sexual abuse, well, that word was just not heard anywhere in Ireland. Strange, because they all knew that children were being sexually abused by those in authority; the government knew, the police knew, the clergy and religious knew, yet nobody could name it. They were afraid of their own shame, and conspired to deny and hide it.

Gerard Mannix Flynn, Nothing to say

Behind the convent gates – Magdalene laundries and hidden abuse

The use of violence was supported by institutions run across Ireland by the Catholic Church and religious organisations. Care and education centres, which were supposed to provide rehabilitation for young people, in reality often functioned as high-security prisons, where children and adolescents were exploited as cheap labour and repeatedly subjected to physical abuse and sexual assault. There are known cases of fatal beatings, prolonged isolation of children from their families, rape, and psychological mistreatment of residents. Among such institutions were the so-called Magdalene laundries, which were meant to help prostitutes or single, often underage mothers with “unwanted” children (whom the nuns frequently took away, claiming they would not be good mothers and did not deserve a child). In a final note to her text, Claire Keegan explains:

Ireland’s or last Magdalen laundry was not closed down until 1996. It is not known how many girls and women were concealed, incarcerated and forced to labour in these institutions. Ten thousand is the modest figure; thirty thousand is probably more accurate. Most of the records from the Magdalen laundries were destroyed, lost, or made inaccessible. Rarely was any of these girls’ or women’s work recognised or acknowledged in any way. Many girls and women lost their babies. Some lost their lives. Some or most lost the lives they could have had. It is not known how many thousands of infants died in these institutions or were adopted out from the mother-and-baby homes. Earlier this year, the Mother and Baby Home Commission Report found that nine thousand children died in just eighteen of the institutions investigated. In 2014, the historian Catherine Corless made public her shocking discovery that 796 babies died between 1925 and 1961 in the Tuam home, in County Galway. These institutions were run and financed by the Catholic Church in concert with the Irish State. No apology was issued by the Irish government over the Magdalen laundries until Taoiseach Enda Kenny did so in 2013.

Claire Keegan, Small Things Like These

What remains after the silence is broken

The Magdalene laundries have become one of the most powerful cultural symbols of institutional violence against women in Ireland. Peter Mullan’s 2002 film The Magdalene Sisters – written and directed by Mullan – shocked public opinion by showing the brutal reality inside those institutions. Joni Mitchell’s protest song The Magdalene Laundries gives a similarly moving and critical voice. The work of Edna O’Brien, though often more indirect, also addresses the fate of Irish women trapped by social and religious systems of control. Together, these works form a layered picture of collective memory and critical reflection on the lives of women in 20th-century Ireland.

To get the best out of people, you must always treat them well, Mrs Wilson used to say.

Claire Keegan, Small Things Like These

If you find my work valuable, you can support it here: