Inspired by a winter read, I decided to spend the summer walking through the streets of London’s East End, which in the late 19th century became the stage for one of the darkest stories of modern times.

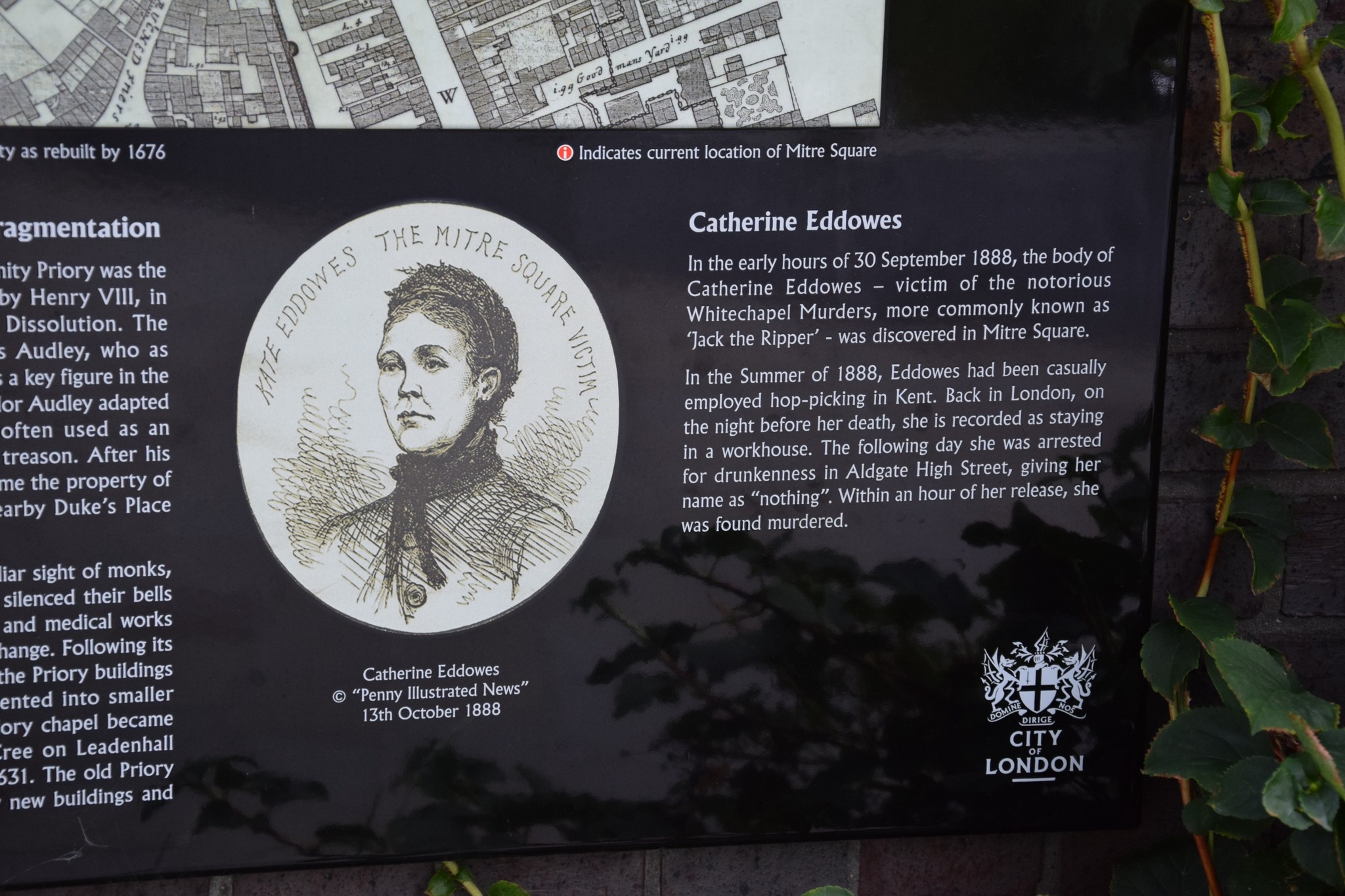

In the summer and autumn of 1888, five women lost their lives in the alleys of Whitechapel: Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly. They all struggled with poverty, homelessness and the lack of support in a world that left no room for weakness. Their deaths were violent and cruel, but the memory of them was quickly overshadowed by the story of the man who killed them.

The Victorian press had no doubts: their fates were explained by what was seen as an ‘immoral lifestyle’. Selling sex on the streets became an easy label that required neither nuance nor empathy. In truth, only two of the women may have turned to sex work at times. The others were simply trying to survive in a world where hunger and homelessness were far greater threats than any personal weakness. The false image created by newspapers meant that, for decades, the women’s identities were reduced to a stereotype, their lives hidden beneath the myth of their killer.

Hallie Rubenhold challenges this myth in her book The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper. Instead of chasing the murderer, as countless writers have done for over a century, she focuses on the victims themselves – their childhoods, relationships, struggles and daily fight to stay alive in poverty. Rubenhold brings them out of the shadows, restoring the dignity denied to them by their contemporaries and by history. It is both an act of remembrance and a gesture of justice – giving back voices to women who were, for so long, treated only as the backdrop to the legend of a ‘dark genius of evil’.

It was the sensational newspapers of the 19th century – the so-called ‘penny press’ – that built the legend of Jack the Ripper. Their pages were filled with loud headlines, supposed letters from the killer, rumours and gossip. Fear and curiosity sold far better than the quiet truth about the lives of poor women in the East End. As a result, it was he, not his victims, who became the focus of public imagination.

Over the years, the Ripper moved beyond criminal history and entered popular culture. His shadow hangs not only over books and films but also, sometimes in grotesque ways, over everyday life. London pubs and restaurants have used his name – for example, the fish-and-chip shop Jack the Chipper, the historic pub The Ten Bells (once renamed Jack the Ripper), or the cocktail bar Ripper & Co in Portsmouth. Tourist marketing and morbid curiosity blend with a dark legacy, transforming tragedy into a decorative spectacle. A story that should serve as a warning has become an ornament.

From time to time, attempts are made to solve the mystery. Modern DNA analysis has suggested that the killer may have been Aaron Kosminski, a Polish Jew and barber from the East End, already suspected during the original investigation. Yet the lack of clear proof and doubts about the methods used mean that his name remains only a theory. Perhaps it is exactly this uncertainty that keeps the legend alive. Today, the Ripper is more of a symbol than a real person of flesh and blood – and his name, turned into a pop culture icon, has sadly drawn attention away from the women whose lives ended in the dark streets of Whitechapel.

All photographs by the author.

If you find my work valuable, you can support it here: