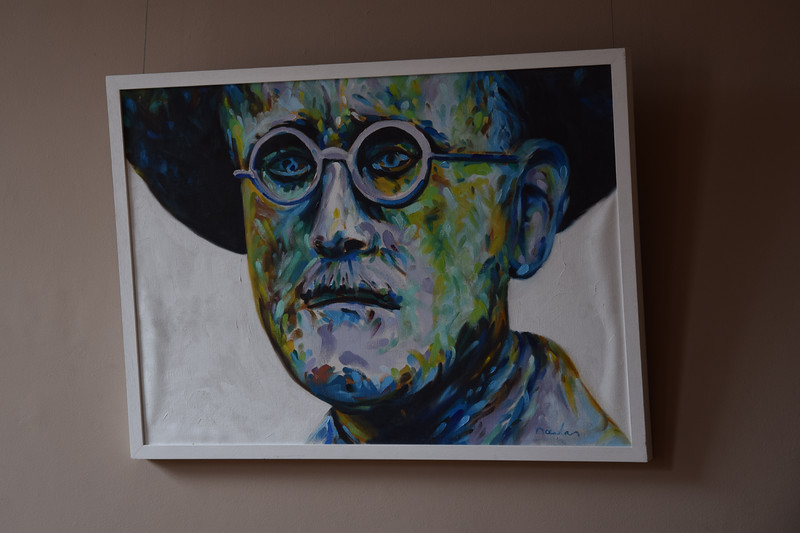

Music in James Joyce’s The Dead

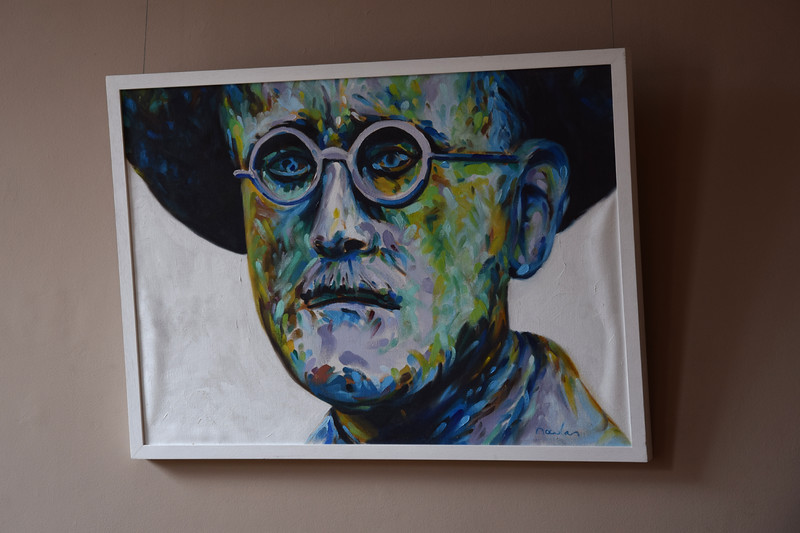

The work of James Joyce is full of music. It is not used only as decoration, but also as a way to express hidden feelings and inner emotions. This is especially clear in the short story The Dead, where Joyce uses the song The Lass of Aughrim to give deeper meaning to the narrative.

Every year, at the beginning of January, I return to both the story and its film adaptation with a feeling of nostalgia. It is a deeply personal story about love, loss and identity, which T. S. Eliot called one of the greatest short stories ever written. When I listen to the old Irish ballad, I often reread the final, most beautiful paragraph of the story. It always fills me with wonder and deep emotion, and it moves me every time. This passage also has a musical quality, as its gentle rhythm and softly flowing melody create an atmosphere of silence, sadness and reflection, bringing the story to a close.

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

James Joyce, The Dead

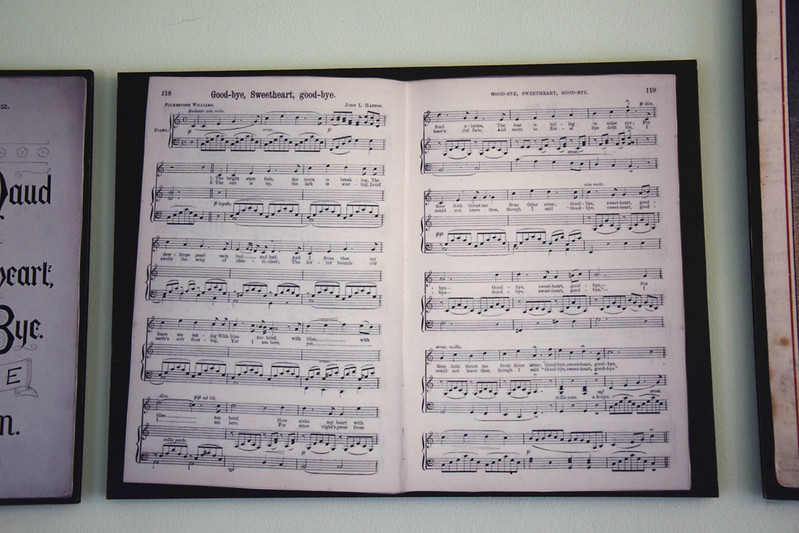

Music is present throughout the entire story, from Italian opera to popular folk songs. Singing, dancing and playing music create the background of the Christmas party, while conversations at the table refer to famous singers and the musical life of Dublin. All of this slowly leads the reader towards the emotional centre of the story.

The Lass of Aughrim in the Story

The song The Lass of Aughrim, heard almost by chance after the party, is not just background music. It becomes a voice from the past that suddenly enters the present. For Gretta Conroy, the song brings back the memory of her first love, Michael Furey, a young man who once sang this song for her and who died tragically young. This memory reveals how strong and sincere that love was, and it clearly contrasts with the emotional distance in her marriage. The past feels more alive and more real than her quiet everyday life.

The song is also essential for her husband, Gabriel, as it leads him to a moment of deep understanding. He realises how empty his emotional life is and understands that the dead can have more power over the living than those who live without strong feelings. In this way, The Lass of Aughrim brings together the main themes of the story – memory, love and death – and leads to a sad, quiet ending that invites deep reflection on human life.

* * *

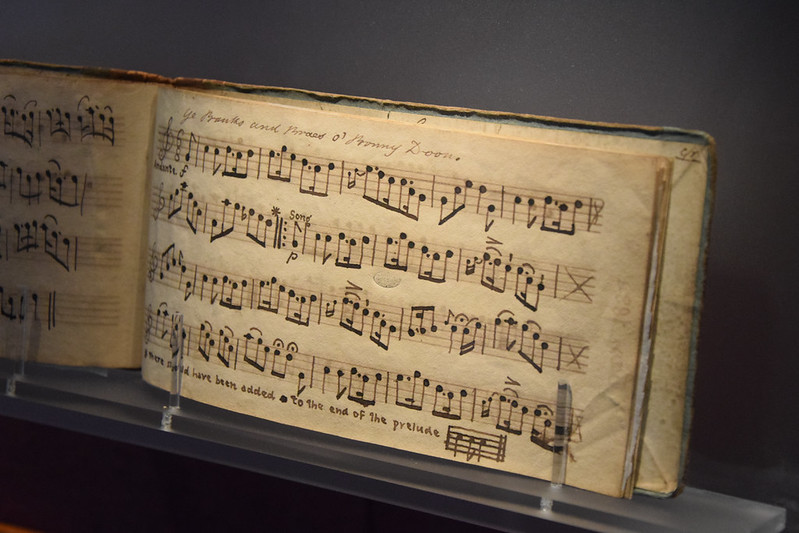

Let the music invite quiet reflection as we listen, accompanied by the restored guitar that once belonged to Joyce himself.

See also: The House of the Dead & Music in the Works of James Joyce

If you find my work valuable, you can support it here: